As a firm of accountants we felt strangely excited to tune into the Chancellor’s press conference last Wednesday, hoping to get a sneak peak of the upcoming budget… but after an hour of monotone prompter reading and rather boring Q&A session, we realised we’d just wasted an hour of our week….

Why this Budget feels different

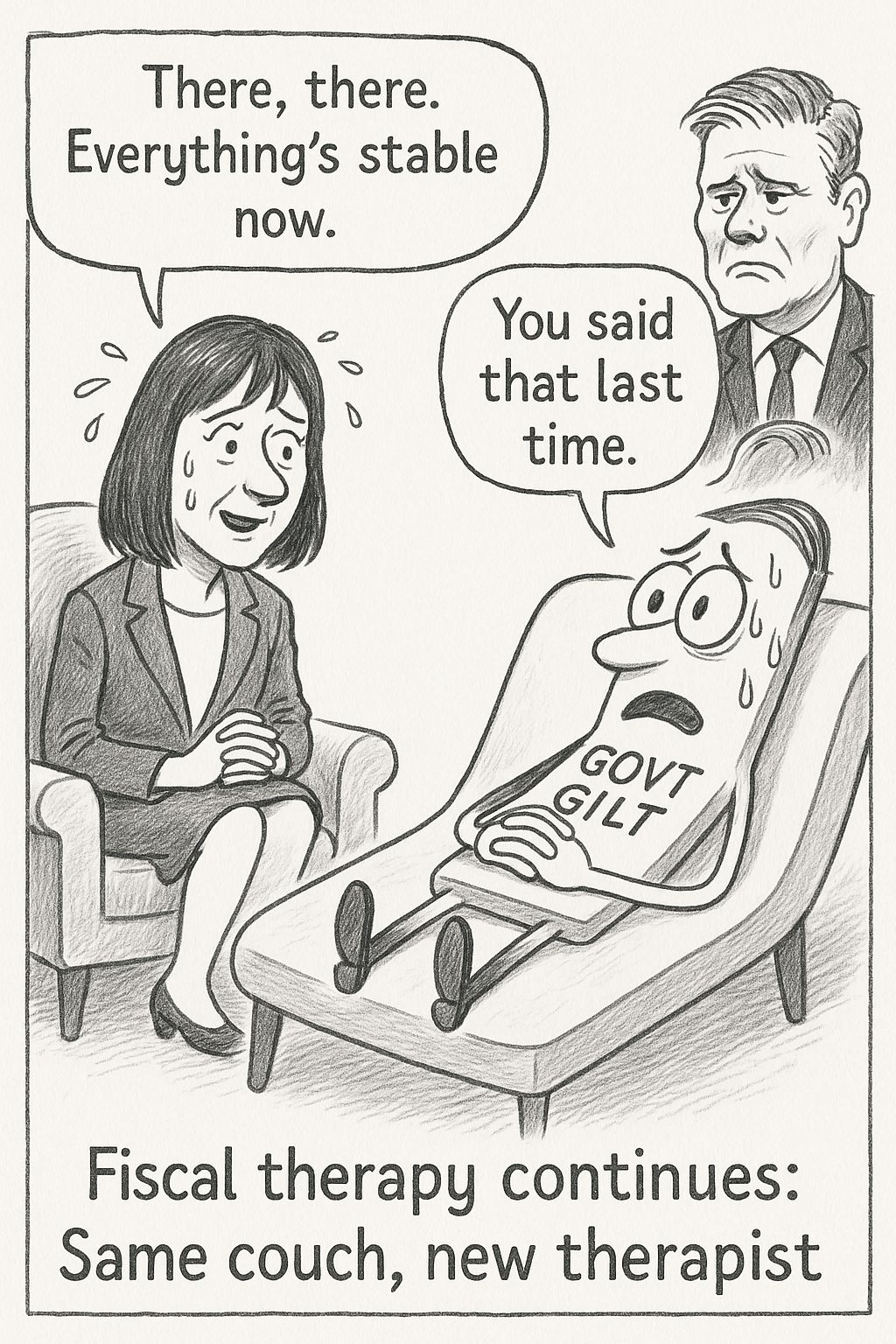

The Autumn Budget on 26th November 2025 is being billed by the Labour Government as a turning point', not for lavish new spending, but for “restoring stability.” Chancellor Rachel Reeves’s address on 5th November 2025 aimed to “prepare the markets” and, in her words, “lay out the choices ahead.”

In practice, it looked like a deliberate attempt to steady nerves in the City and calm any twitchiness in the gilt markets – the sort of jitters that famously helped sink the Liz Truss mini-Budget experiment. There’s also a bit of Westminster choreography at play: Reeves appears keen to make herself synonymous with fiscal stability, effectively branding herself as the person who keeps Britain’s finances strapped into their seatbelt. As one pundit in Whitehall put it, she’s making herself “too stable to sack” – a signal to both the markets and to Starmer that she’s the human embodiment of “steady as she goes.” A touch theatrical perhaps, but given the market’s collective trauma from 2022, it’s a political move few would begrudge.

The key phrase underpinning all this, and the reason the Budget narrative is so cautious, is headroom, the Treasury’s genteel term for how much wiggle room a Chancellor has before breaking her own fiscal rules.

The headroom problem (as the Government tells it)

“Headroom” means the gap between what the Chancellor plans to spend and the fiscal limits she’s set for herself to keep the numbers looking respectable. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), that buffer currently stands at about £9.9 billion – respectable in normal life, but in government arithmetic it’s roughly the equivalent of finding a tenner behind the Downing Street sofa.

For context:

George Osborne often had £25–30 billion of breathing room before 2016.

Philip Hammond worked with roughly £15–20 billion.

Rishi Sunak lost headroom entirely during the pandemic (understandably)

Even Jeremy Hunt’s 2023 Autumn Statement offered around £13 billion of space.

Reeves’ £9.9 billion is therefore wafer thin. Add higher debt-interest payments, slower growth forecasts and a backlog of delayed spending commitments, and that cushion could vanish faster than a pothole-repair fund in February.

Between the spreadsheets and the backbenches

Even if Reeves wanted to tighten the purse strings, she faces a Labour backbench majority with little appetite for spending cuts. This is not a party renowned for its enthusiasm for austerity, and early hints that welfare reform or departmental savings might fill the gap have already met quiet resistance.

That leaves the Chancellor short on levers. If cuts are politically unpalatable and borrowing costs remain high, the only route left to plug the hole – and to begin nudging the debt ratio down – is through tax rises. Reeves hasn’t said it outright, but her speeches and selective briefings seem designed to prepare both the markets and the public for that inevitability: fewer cuts, more contributions.

Economists at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) have already warned that Reeves faces an “impossible trilemma” between raising taxes, cutting spending, or breaking her fiscal rules, arguing that “substantial tax rises” will be needed to stabilise the public finances (Sky News).

Why there’s “another hole” in the public finances

When the previous Budget was published, the Chancellor had roughly £9.9 billion of headroom – a wafer-thin buffer, but technically still within bounds. Since then, several factors have eaten through it:

Higher interest costs. Market rates have remained elevated, meaning the Treasury is spending billions more on debt interest.

Unfunded commitments. Promises around welfare and winter-fuel payments never materialised into reforms, so the spending continues – adding about £10 billion to outgoings.

New pledges. The decision to remove the two-child limit on certain benefits and similar commitments add roughly £5 billion more.

Weaker growth. The OBR is expected to downgrade productivity and growth forecasts, cutting expected tax receipts by another ~£10 billion.

Add it up, and what began as a £9.9 billion cushion becomes roughly a £17 billion hole – a swing of nearly £27 billion. As Sky News explained in its recent analysis (watch here), “you’re a long way short – and it could be even worse.”

In practical terms, that means the fiscal rules are already broken on paper. To restore them, Reeves either has to raise taxes, delay spending, or rewrite the rules entirely. Given the political and market optics, the first option looks by far the most likely.

As such, this Budget looks less like an economic revolution and more like a balancing act – a pragmatic attempt to look serious about the numbers while keeping her party (and the bond markets) calm.

Areas worth watching – and what’s actually being discussed

Income Tax & Personal Allowances

If the personal allowance (£12,570) and higher-rate threshold (£50,270) stay frozen until 2028, the average worker earning £35,000 will pay roughly £650 more in income tax next year purely through “fiscal drag.” A 1p rise in the basic rate (to 21%) would raise around £7 billion, but cost a typical full-time earner another £250 – £300 a year. Freezing thresholds is the stealthier option – less headline-grabbing, but almost as lucrative.

Reeves is expected to offset a 2p rise in income tax with a 2p cut in national insurance in an attempt to shift the burden of the tax rises onto other groups such as pensioners and landlords.

Pensions and the quiet temptation of reform

While not a headline issue, pensions remain a tempting lever for any Chancellor trying to raise money without announcing a “tax rise.” Speculation has centred on two potential areas of change:

The 25% tax-free lump sum

Currently, individuals can withdraw up to a quarter of their pension pot tax-free on retirement. There’s growing chatter in policy circles, particularly from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and the Resolution Foundation, that this long-standing perk could be “reviewed” in the name of fairness.

Cutting or capping it would instantly raise billions in extra income tax receipts, though at the political cost of being accused of breaking yet another “middle Britain” promise.

So far, neither Reeves nor Starmer have ruled it out explicitly, which is perhaps more telling than any official denial.

(RIP 25% of wealth managers’ AUM)

Tax Relief & Salary Sacrifice

Higher-rate tax relief on pension contributions is also in the Treasury’s crosshairs. One rumoured approach, (outlined in The Telegraph and MoneyWeek), is to cap effective annual relief at £2,000 per person by limiting the benefit from salary sacrifice schemes.

That would affect both directors and employees who use pension contributions as a tax-efficient form of remuneration, particularly in small and mid-sized companies.

If adopted, it would amount to a quiet erosion of higher-rate relief rather than a headline-grabbing overhaul, politically neater, but no less significant for long-term savers.

As with much of this Budget, it’s a case of “watch what they don’t deny.” When the Treasury stays silent on an idea, it’s usually because it’s sitting somewhere in the modelling spreadsheets.

National Insurance & LLP Structures

The Treasury is considering an employer-style National Insurance charge on LLP members’ profit shares, aligning partnership income with PAYE employment. At 13.8 %, this could raise £1.5 – 2 billion a year. Both the Financial Times and Guardian frame it as part of a “fairness” drive closing the gap between self-employed professionals and salaried staff. (Financial Times)

Capital Taxes – CGT, IHT & Wealth-Related Measures

Aligning CGT with income-tax bands could see the top rate jump from 20 % to 40 %, particularly on share or property disposals. Meanwhile, trimming Business Asset Disposal Relief from £1 million to £500,000 would double the tax bill on many SME exits. The IFS calls it “simplifying distortions”; (IFS, )

Corporation Tax & Investment Incentives

While the main rate (25 %) is unlikely to move, the Government may revisit the small-profits threshold (£50,000) and marginal-relief band (£250,000). If those limits are frozen again, more mid-sized companies will drift into the full-rate bracket.

Combined with potential tightening of full expensing and R&D relief rules, effective rates could edge higher over the next two years even without an official increase. Changes to R&D could reclaim £1–2 billion by narrowing definitions and upping documentation requirements. (Financial Times, Resolution Foundation)

VAT, Property & Consumption

The VAT registration threshold (£90,000) looks set to stay frozen – quietly pulling thousands more small firms into scope each year. At the same time, SDLT reliefs on second homes and council-tax bands frozen since 1991 are under review, with local authorities pushing to modernise them. (Morningstar)

Final word

At this stage, we can only comment on what’s been briefed, hinted or speculated in the run-up to the announcement. Until the Chancellor sets out the details, the true direction of policy, and who ultimately foots the bill…. remains to be seen.

With the PM unable to double down on manifesto promises, and barely £10 billion of fiscal headroom and limited appetite for spending restraint, it seems clear that tax will do most of the heavy lifting. The real question is not whether the burden rises, but how quietly it happens.

We’ll publish a follow-up blog shortly after the Budget with a clear summary of confirmed measures, threshold movements and practical implications for our clients.

For any queries, drop us an email.